What Is Transparency in AI Safety?

- kanna qed

- 2025年12月22日

- 読了時間: 10分

Transparency in AI Safety Is a Finite Procedure

1. Defining It Through Reproducibility, Non-Posthocness, and Auditability

Consider a scenario where post-incident verification of an AI model becomes impossible. When a bug or bias is discovered in a system, developers may swap out the model or adjust thresholds after the fact, making it impossible to reproduce the same conclusion from the original output. Although an explanatory report is submitted at the time of the incident, the crucial model behavior has already been altered, preventing any third party from conducting a follow-up verification of the judgment made at the time of the accident. Furthermore, even if a vast amount of explanatory documentation and visualization graphs are provided, these alone do not necessarily enhance verifiability. In fact, as “explanations” proliferate, the discussion often becomes more complex, potentially obscuring the locus of responsibility and the identification of root causes. In situations where fairness and safety indicators are adjusted ad hoc to justify that “in hindsight, there was no problem,” no amount of explanation can ensure true transparency.

Why does transparency remain elusive despite increasing explanations? It is because the lack of transparency is not a problem of “insufficient understanding” but is essentially about the system being “manipulable after the fact.” As long as criteria and evaluation axes can be replaced post-hoc, no matter how detailed the explanation provided, it cannot be considered transparency in the true sense. In other words, transparency does not simply mean that “the interior is visible”; rather, it refers to the requirement that the basis for results and evaluation procedures remains unfalsifiable after the fact.

2. Defining Transparency (Separating from the Black-box Problem)

In this article, we define transparency according to the following three conditions (and will not deviate from these definitions):

Transparency: A state where a third party can reproduce the same conclusion using the same input and the same procedure, where criteria or explanations cannot be replaced after the results are observed, and where the scope of “explanatory reach” is fixed within a finite range.

Black-box Problem: Refers to the challenge where the internal representations of a model cannot be intuitively interpreted. While it is a factor related to transparency, opacity can persist even if the model is not a black box (i.e., its interior is visible as a white box) if the evaluation procedure is not fixed.

The “Enemy” (“Infinite Evasion”): This is viewed not as a specific actor undermining transparency, but as a structural problem. Typical examples include the “infinite postponement of evaluation criteria,” “shifting of evaluation axes,” and the “disempowerment of the verifying entity (third party)” — mechanisms through which explanations and criteria can evade definitive assessment indefinitely.

It is crucial to emphasize that Explainability and Transparency are not synonymous. Being able to explain internal states or reasons for judgment to humans (explainability) is important, but it does not guarantee transparency. For example, even with a “white box” model where the internal structure is public, it remains opaque if the evaluation criteria can be replaced after the fact. Conversely, even if the interior is a black box, transparency can be ensured if the procedure is fixed in advance and verifiable by a third party. In short:

Explainability $\neq$ Transparency

Transparency = Verifiability + Pre-fixed Procedures

Transparency is not about “visibility” but about “fixity” and “third-party verifiability” [1][2]. Centering on this definition, we proceed by distinguishing the black-box problem from the core essence of transparency.

3. The Structure of “Infinite Evasion” That Destroys Transparency

The enemy of transparency is not a specific individual or organization, but a structural design that allows for infinite evasion. Here, we list six typical patterns of “infinite evasion” that undermine transparency:

Post-hoc Criteria: Changing or replacing evaluation criteria and thresholds after seeing the results.

Unlimited Addition of Conditions: Continuously adding new exception conditions whenever an inconvenient result arises.

Infinite Expansion of Discussion Scope: Expanding the points of contention one after another, ultimately making it impossible to pin down the actual problem.

Disempowerment of the Verifying Entity: Restricting information and means so that third parties cannot conduct follow-up tests or verification.

Shifting Definitions: Changing the definitions of key terms midway through a process to shift the focus of the discussion.

Postponement of Judgment (Time Postponement): Infinitely delaying evaluation and explanation by claiming that issues will be “addressed in the future.”

Such “infinite evasion” is the true enemy of transparency. To put it bluntly, the enemy is not the complexity of the model, but a design that allows for the infinite post-hoc introduction of criteria and explanations. No matter how much one simplifies or visualizes the model, if the evaluation procedure remains infinitely changeable, transparency is unattainable. Conversely, unless this “infinite evasion” is contained, any explanation or audit will result in empty rhetoric.

4. The Role of $\zeta$-structure in Exposing Infinite Evasion

What is needed to contain this “infinite evasion”? The key lies in the role of a mathematical layer we call the $\zeta$-structure. While it may sound complex, we describe the $\zeta$-structure here as a device that aggregates and exposes infinitely extending factors within a single point of reference.

When considering model behavior, discrete factors (individual events, threshold crossings, exceptional occurrences, etc.) and continuous factors (probability distributions, frequency characteristics, continuous changes in hyperparameters, etc.) are often intermingled. Usually, when attempting explanation or evaluation, these factors merge into elements that may appear as infinite terms or infinite products. This is the breeding ground for “infinite evasion.” In an opaque design, explanation candidates and room for adjustment appear to exist infinitely.

The $\zeta$-structure treats both discrete and continuous factors within the same field of view, binding infinitely extending contributions (sums or products of infinite terms) into a single functional form. For example, it analyzes model behavior from both the frequency domain and event frequency, collapsing them into an integrated indicator. The role of the $\zeta$-structure is to aggregate these scattered infinite “escapes.” Crucially, the $\zeta$-structure is not a “magic function that explains everything.” Rather, $\zeta$ is a function that points to a finite window (range): “To what point should we cut off for the process to become non-manipulable?” Even explanations that appear infinite, when expressed through the $\zeta$-structure, reveal a point where further contributions cease to have significant meaning. In other words, the $\zeta$-structure visualizes infinite evasion and defines the range that must undergo “finite closure.” The specific mechanism for this finite closure is the Beacon window, described in the next section.

5. Finite Closure (Beacon Window): The “Cutting Point” for Establishing Transparency

The Beacon window (finite closure) is a window that finitely fixes the scope of observation in response to “infinite evasion.” To establish transparency, certain elements must be fixed at a minimum within the evaluation procedure:

Observation/Evaluation Window: Defining the specific period and data range targeted for evaluation (Evaluation Window).

Evaluation Protocol: Pre-defined agreements such as the order of preprocessing, data normalization methods, and definitions of derived indicators.

Evaluation Function: Indicators and thresholds for determining pass/fail (OK/NG) status (e.g., a “pass” requires a specific bias indicator to be 0.8 or higher).

Outward Rounding Policy: Computational procedures for rounding toward the safe side when uncertainty persists (e.g., establishing safety margins in risk assessment).

Setting a Beacon window means fixing these “procedural windows” in advance. This cuts off any room for evaluators or model developers to conveniently alter criteria after the fact. Transparency cannot be established unless the scope of observation (the reach) is fixed. If the evaluation range is ambiguous, infinite evasion — such as claiming “this case was out of scope” or “it’s fine if we change the conditions” — becomes possible. The Beacon window structurally blocks these escape routes and serves as a “cutting point” that creates the prerequisite for transparency by partitioning the evaluation reach finitely.

To be clear: “transparency” without a fixed window is not transparency. Without a fixed evaluation window, conclusions can be manipulated post-hoc to any degree [3]. Establishing transparency requires defining the evaluation window and rules as immutable. The model is then evaluated and explained within that fixed range, and anything outside it is clearly delineated as being “beyond the explanatory reach.” For the first time, through the Beacon window, transparency is achieved where “what can and cannot be said” is determined within a finite range.

6. ADIC/ledger: Implementing Transparency as a “Certificate”

Once the evaluation window and procedures are fixed, they must be recorded as a certificate that can be verified by a third party. We propose that the output of transparency should not be a mere text report, but a combination of a certificate and a verification script [4]. Specifically, an audit certificate containing the following content is issued after evaluation:

Identification of Input Data: Specifying the version of the dataset or input used (hash values, data signatures, schema information).

Identification of Execution Code: The code for the model and scripts used (repository commit IDs, hash values).

Identification of Execution Environment: Library and dependency information, runtime version information (container hashes, etc.).

Threshold Policy: A declaration of pre-fixed evaluation indicators, thresholds, and pass/fail criteria.

Beacon Window Specifications: Detailed specifications of the applied window, including the evaluation window and preprocessing protocols.

Calculation Log (ledger): Records of the results of each calculation step, boundary values, and final judgments (including error ranges where necessary).

Verify Procedure: Procedures for a third party to re-execute the same evaluation with a single command (e.g., providing verification scripts or Docker images).

This collection is regarded as the certificate and is published and preserved. Along with the certificate, a verification script is provided so that anyone can reproduce the model evaluation results [4][5]. For example, a set consisting of certificate.json, ledger.csv, and verify.py is produced as the output. A third party can download these and run verify.py --cert certificate.json to reproduce the same conclusion [4].

To re-verbalize the criteria for transparency: Transparency refers to a state where a third party can conduct a follow-up test of the results through this certificate and verification procedure. Conversely, opacity is a state where any of the above elements are missing, preventing third-party reproduction of the conclusion. No matter how exhaustive an explanation may be, if there is no certificate and the results cannot be reproduced by others, the process remains opaque. By distilling transparency into a “certificate + verifiability” protocol, accountability gains objective collateral [4].

Figure 1 schematically illustrates this series of concepts. The left side shows the structure of opacity in conventional model operations, with “infinite evasion” (post-hoc thresholds, rampant post-hoc explanations, expansion of scope, unverifiable evaluation) depicted as clouds at the top. The center shows the state where the evaluation scope, protocols, and indicators are finitely fixed by the Beacon window. The right side shows a transparent process where third-party auditing is enabled through certificates, ledgers, and verification scripts. Items marked with a checkmark (✅Reproducible, ✅Non-manipulable, ✅Finite reach) represent the fulfillment of the three conditions for transparency.

Figure 1: Transparency as a Finite Procedure — In the proposed method, transparency is realized by fixing the reach and procedure of evaluation finitely and enabling follow-up tests by third parties through certificates and verification.

7. Case Studies: The Effects of Finite Closure

In addition to theoretical discussion, we demonstrate the practical efficacy of this method through two specific cases.

Case A: Response to Model Degradation (Drift) During Operation — Conventionally, when accuracy drops or bias is discovered, “explanations” like feature importance are often added after the fact while thresholds are quietly adjusted. This makes the evaluation criteria fluctuate, rendering the process opaque. By applying our method, the evaluation period and criteria are fixed in advance via a Beacon window, and the threshold policy is made unchangeable, with all judgment processes recorded in the ledger. This structurally eliminates the room for conveniently shifting criteria during operation, making the evaluation and rectification process transparent.

Case B: Improvement in Operation of Safety and Bias Indicators — In typical practice, whenever problems are found in fairness or safety scores, those definitions and thresholds are often changed under the guise of “improvement” to justify results post-hoc. This constitutes post-hoc optimization and undermines transparency. In our method, an evaluation protocol fixing these indicators is formulated and certified. Once issued, changes to indicators not described in the certificate are invalid (non-manipulable), preventing the evaluation axis from being shifted. Third parties can always refer to the certificate to verify the criteria, ensuring that safety and bias evaluations are conducted continuously and transparently.

8. Implementation Roadmap: Steps for Introducing a Transparency Protocol

The following minimum implementation steps serve as a roadmap for introducing this approach into the field. These can be initiated within a single development sprint:

Fixing the Evaluation Protocol: Decide on the indicators, thresholds, data scope, and preprocessing protocols, and fix them in advance through documentation (setting the Beacon window).

Identification of Input Data: Assign hash values or versions to datasets and input information to ensure the same data can be retrieved later. Solidify input conditions, including schemas and preprocessing.

Identification of Code and Environment: Snapshot and record the model code, scripts, dependent libraries, and execution environment (Git commit IDs, Docker image IDs). This allows third parties to reproduce the exact setup.

Implementation of Ledger Output: Incorporate a function to output each calculation step and the basis for the final judgment to a log file (ledger). Record boundary values and error factors to allow the judgment process to be fully traced.

Preparation of Verify Scripts: Create a script (e.g., verify.py) that allows a third party to reproduce the evaluation with a single command using the certificate and ledger. This enables auditors to conduct follow-up tests without manual intervention.

Following these steps introduces a verifiable transparency protocol rather than a mere explanatory report. Step 1 — fixing the evaluation axis — is the essential core. Subsequent steps are technical implementations to guarantee that fixity. This roadmap serves as a checklist; if any step is missing, complete transparency cannot be claimed.

9. Conclusion

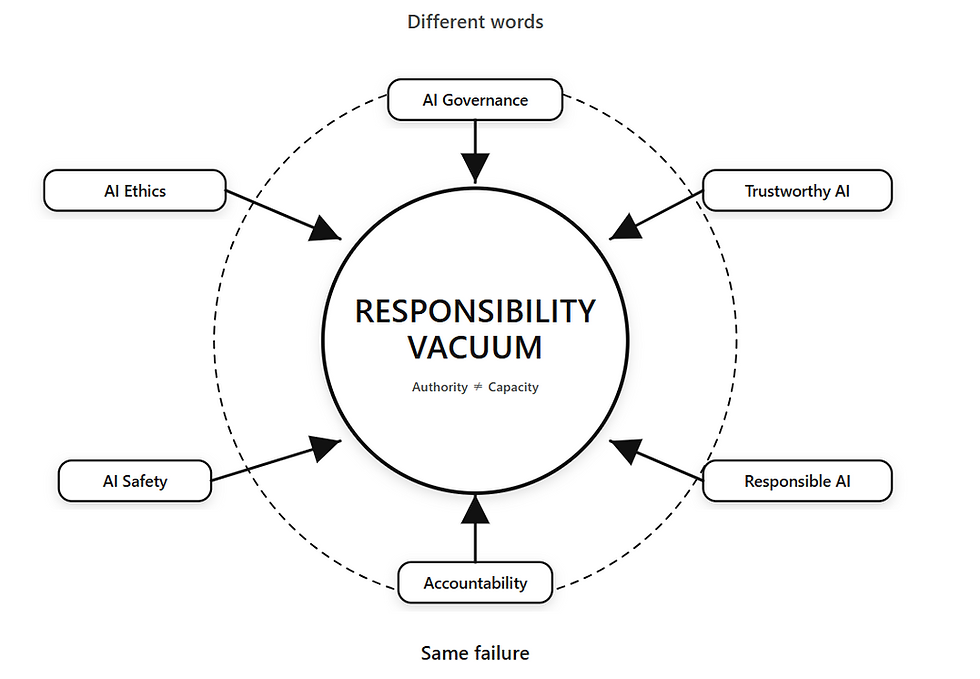

Transparency is not “understanding” but “unalterable reproduction” — this is the core claim of this article. While enriching explanations is beneficial, if procedures are not fixed, infinite escape routes will inevitably emerge. By exposing the structure of infinite evasion through the $\zeta$-structure, fixing the evaluation reach through finite closure (the Beacon window), and recording it as a third-party verifiable certificate through ADIC/ledger, transparency is guaranteed. Transparency $\neq$ Explanation; Transparency = Fixing of Procedures + Reproduction Verification by Third Parties [4][3]. We expect this transparency protocol to become a new standard in the practice of AI governance and model auditing.

References

Mökander et al., “Auditing large language models: a three-layered approach.” AI and Ethics, 4:1085–1115, 2024. (A three-layered model for governance, model, and application auditing of LLMs).

Laine, Minkkinen, Mäntymäki, “Ethics-based AI auditing: A systematic literature review on conceptualizations of ethical principles and knowledge contributions to stakeholders.” Decision Support Systems, 161:113768, 2024. (Organizes definitions of ethical principles (transparency, etc.) in AI auditing and knowledge for stakeholders).

Agarwal et al., “Breaking Bad: Interpretability-Based Safety Audits of State-of-the-Art LLMs.” NeurIPS 2025 Workshop on Lock-LLM, 2025. (A method for detecting vulnerabilities through intervention (steering) in internal representations in addition to black-box testing).

Schnabl et al., “Attestable Audits: Verifiable AI Safety Benchmarks Using Trusted Execution Environments.” ICML 2025 Workshop on Technical AI Governance (TAIG), 2025. (A framework for executing safety benchmarks on TEEs and cryptographically proving that evaluation was conducted correctly).

O’Gara et al., “Hardware-Enabled Mechanisms for Verifying Responsible AI Development.” ICML 2025 Workshop on TAIG, 2025. (A roadmap proposal for making the AI development process itself verifiable through hardware mechanisms (location verification, network verification, workload verification, etc.)).

コメント