What is the Data Bias Problem in AI Safety?

- kanna qed

- 2025年12月22日

- 読了時間: 6分

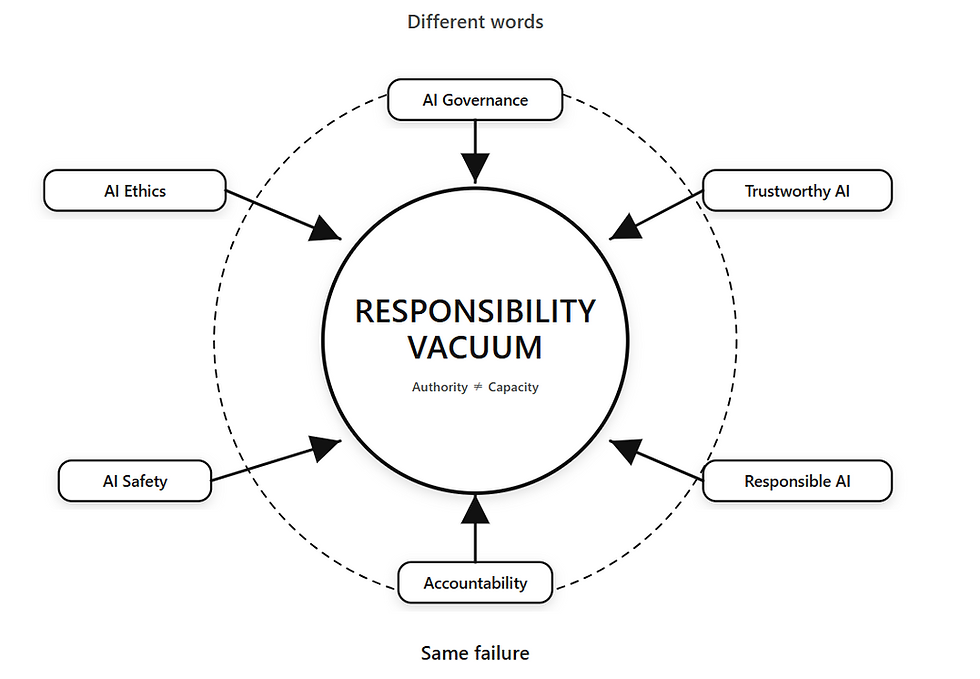

The Core Issue: Data bias is not merely a “failure of learning” but a “failure of responsibility,” posing a severe threat to the safety of AI systems. Biased AI outputs can amplify discrimination and undermine public trust [1][2].

The Structural Problem: The bias problem is insidious because it allows responsibility to “slip backward” infinitely — one can always defer accountability by citing another potential cause (more data, more features, etc.). The buck never stops.

The Mathematical Solution: The Riemann Zeta function ($\zeta$) integrates discrete “causes” (primes) and continuous “effects” (the spectrum of zeros) into a single identity, allowing for a reversible separation of the two. By emulating this, we can define finite responsibility boundaries for AI bias through “Finite Closure.”

The excuse that “there might be bias” can be made infinitely. Therefore, what matters is not the mere existence of bias, but the “responsibility boundary” that fixes that bias as finite evidence.

1. Reconceptualizing Data Bias as an AI Safety Threat Model

To address the data bias problem, we must first redefine it as a threat to AI safety. It is not just about model accuracy; it is about managing the upper bound of harm a biased AI can inflict. The goal is “guaranteed management of harm limits” — ensuring that AI systems do not unfairly cause disproportionate harm to specific groups.

Key types of bias from a safety perspective include:

Sampling Bias: Skewed data collection where certain populations are under- or over-represented.

Measurement Bias: Distortions in the sensing or labeling process due to faulty equipment or skewed evaluation criteria.

Label Bias: Bias in ground-truth data reflecting the subjective prejudices of annotators or historical institutional inequities.

Feedback Loop Bias: Cases where AI outputs influence future input data, self-amplifying bias in closed loops (common in recommendation systems).

Domain Shift (Environmental Change): Performance degradation for specific groups when the data distribution changes between training and deployment.

In all cases, the essence of the concern is that “systematically higher error rates or harm for specific groups” allow problems to be postponed indefinitely without anyone assuming responsibility [3][4]. Even when people are disadvantaged by an AI’s judgment, the structural tendency is to move to the next “improvement” while claiming “the data might have been biased,” leaving accountability ambiguous.

2. Infinite Regress: The Structure of Deferred Responsibility

The difficulty of the bias problem lies in how debates over its existence often fall into an “infinite loop” of deferred responsibility:

“It will be solved if we collect more data”: While common, the definition of “enough” is perpetually absent. As long as data collection continues, the excuse that “it might still be insufficient” remains available.

“It will be solved if we add more features”: There is no fixed point for what constitutes a sufficient feature set, leading to an endless cycle of adding attributes.

“It will be solved if we rebuild the model”: Retraining lacks a clear “fairness goal line.” Even if metrics improve, the fear that “other biases might be lurking” keeps the model in an infinite cycle of re-learning.

Consequently, the “boundary” for when an AI’s judgment can be trusted remains undefined [5][6]. To break this cycle, we need Beacons (reference points for truncating observation) and Windows (defined ranges) to fix bias as Finite Evidence (Certificates). This process determines the presence and impact of bias within a specific scope and finalizes the responsible entity.

3. The Zeta Function: Separating “Cause and Effect”

In number theory, the Riemann Zeta function is a unique bridge between primes (discrete causes) and zeros (the spectrum of continuous effects). The power of the $\zeta$-function lies in putting discrete causes and continuous effects into the same domain and making them reversible.

Through the Explicit Formula of the $\zeta$-function, a “measurement $F$ of prime distribution” can be decomposed into three terms:

$$F = M + S + R$$

$M$ (Main term): Represents the global average behavior; the smooth curve expected if primes did not exist.

$S$ (Spectral term): The sum of oscillatory contributions from all non-trivial zeros. This is where the “bias” caused by primes is expressed as structured fluctuations (modes).

$R$ (Residual): The “remainder” that cannot be explained by the first two. Theoretically, this can be reduced to an infinitesimal error.

This formula implies that “deviation caused by primes” is not merely an error but can be treated as an identifiable spectral structure [7][8]. By decomposing the influence of causes (primes) on effects (fluctuations) into a single equation, we can confine the remainder into a “Finite Responsibility Domain.”

Translating to AI Bias

Applying this $\zeta$-style approach, we categorize the bias $B$ latent in AI systems into three contributions:

Main Term Deviation ($B_{main}$): Deviation from the expected neutral standard (e.g., the population average), representing global structural skew.

Spectral Term Deviation ($B_{spec}$): Systematic bias appearing in specific modes — institutional factors, repetitive selection processes, or seasonal patterns.

Residual ($B_{res}$): Unexplained bias that must ultimately be contained within a finite bound.

For example, a 2025 Nature paper demonstrated how Large Language Models (LLMs) reinforce gender and age stereotypes [7]. When ChatGPT was asked to create fictional resumes, it unfairly depicted women as younger and less experienced than men, even with identical career backgrounds [7][9].

Bias is not about whether it is “completely eliminated,” but about decomposing which contributions remain and fixing them as finite evidence.

4. The Finite Closure Approach to Bias Responsibility

4.1 $\zeta$-Style Accountability

Accountability is established by decomposing the bias metric $B$ and defining the responsibility range as finite. The residual $B_{res}$ is the “Responsibility Range” we must manage, ensuring it remains below a pre-agreed threshold. This allows us to present “how much bias remains” as finite evidence.

4.2 Beacons and Windows: Mechanisms for Closure

To close the infinite regress, we define:

Beacon: The point in time or condition where bias is measured and fixed (e.g., “per model release” or “annual evaluation report”).

Window: The scope (time, data, or group) within which responsibility is finalized (e.g., “output logs from the last six months” or “comparison of attributes A and B”).

By designing Beacons and Windows, we create a boundary that says, “We stop here.”

4.3 Certificates and Auditability

The results are recorded as Certificates, containing:

Data Identification: Dataset versions, hashes, and filters (e.g., period/region).

Preprocessing/Feature Info: Procedures, parameter IDs, and attribute lists used for engineering.

Decomposition Results: Values for $B_{main}$, $B_{spec}$, and the upper bound of $B_{res}$ [10].

Decision Policy: OK/NG status based on pre-defined thresholds (e.g., “Pass if $B_{res} \leq 0.02$”).

Verification: Procedures for third-party auditors to reproduce the evaluation [11].

5. Case Study: Group Error Disparity

Consider a medical AI where the misdiagnosis rate differs between Race A and Race B [12][13]. Traditionally, this leads to vague demands for more data.

Under Finite Closure, the team issues a certificate showing:

$B_{main} = 0.05$ (global skew), $B_{spec} = 0.02$ (institutional patterns), and $B_{res} \leq 0.01$.

If the threshold was $0.02$, the bias is declared “managed.” This shifts the debate from the theological “is it perfectly fair?” to the verifiable “how much unexplained bias remains?”

6. Comparison with Recent Research

Our $\zeta$-analogy approach complements current trends in AI safety:

NIST Bias Management Standards (2022): NIST SP 1270 provides a framework for identifying bias [11]. Our proposal adds a mathematical “Responsibility Boundary” to define when identified bias is “safe enough.”

Responsible AI Research (Google/Stanford): Recent work emphasizes “Built-in Design” for safety and accountability [17][18]. We extend this by focusing on operational proof post-deployment via mathematical decomposition.

Advanced Detection Tools: While 2024/2025 studies (e.g., Nature 2025) focus on detecting stereotyping [7][19], our approach addresses how to legally and ethically “fix” that responsibility using the certificate model.

7. Conclusion: Challenging AI Bias with Finite Boundaries

Data bias is the front line of AI safety. By applying the $\zeta$-function’s logic of separating cause and effect, we can stop the infinite regress of excuses and establish “Finite Closure.”

Defining a point where we say “the remaining bias is at this level” allows for steady, iterative improvement rather than chasing a moving goalpost. Building a foundation where developers and society can agree on what constitutes “safe enough” is the only path to truly Responsible AI.

References

[1] Schwartz, R., et al. (2022). Towards a Standard for Identifying and Managing Bias in Artificial Intelligence. NIST SP 1270.

[2] Guilbeault, D., et al. (2025). Age and gender distortion in online media and large language models. Nature, 646(8087), 1129–1137. [7][8][9]

[3] Ferrara, E. (2024). Fairness and Bias in Artificial Intelligence: A Brief Survey of Sources, Impacts, and Mitigation Strategies. Sci, 6(1), 3. [12][13][23]

[4] HAI Stanford (2024). AI Index Report 2024, Chapter 3. [5][6][14][15][16]

[5] LinkedIn (2024). How to Create Bias-Resistant Risk Management Programs. [10]

[6] Russell, et al. (2025). Bias, Safety, and Accountability by Design: Ensuring Ethical AI Systems. [17][18]

[7] ACM FAccT (2024). Impact Charts: A Tool for Identifying Systematic Bias. [19]

[8] ACM FAccT (2024). Fairness Feedback Loops: Training on Synthetic Data Amplifies Bias. [20]

[9] NIST (2022). SP 1270: Standard for Identifying and Managing Bias in AI. [11][21][22]

コメント